Available At

View Location

We provide diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy services with wide spectrum.

Substernal burning after meals or at night, associated occasionally with regurgitation of gastric juices, is one symptom. Discomfort is relieved by standing or sitting. Dysphagia, a late complication of GERD, is caused by mucosal edema or stricture of the distal esophagus. However, no symptom is specific for GERD, and therapeutic decisions should not be made on symptoms alone.

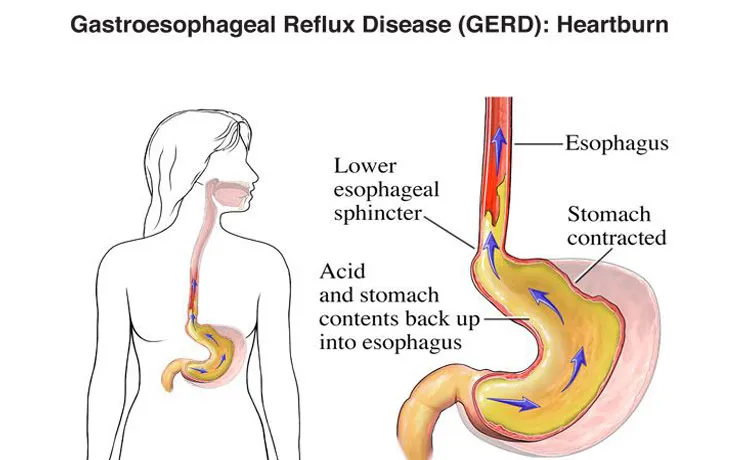

The underlying abnormality of GERD is functional incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which allows gastric acid, bile, and digestive enzymes to damage the unprotected esophageal mucosa. Achalasia, scleroderma, and other esophageal motility disorders are sometimes associated with GERD.

Usually, classic clinical symptoms are enough to start initial symptoms. Endoscopy with biopsy is essential in diagnosing GERD. Barium swallow with or without fluoroscopy can diagnose reflux but cannot identify esophagitis. Twenty-four-hour esophageal pH testing associates reflux with symptoms and is useful in some patients. Gastric secretory or gastric emptying tests are occasionally helpful. Manometry of the esophagus and LES is required whenever an esophageal motility disorder is suspected and before any surgical intervention.

No. Not all patients with GERD have a hiatal hernia, and not all patients with a hiatal hernia have GERD. A total of 50% of patients with GERD have an associated hiatal hernia.

About 50% of patients show significant healing with H2 blockers, but only 10% of these patients remain healed 1 year later. Metoclopramide promotes gastric emptying but rarely relieves symptoms consistently in the absence of acid reduction.

Failure of nonoperative (medical) therapy is the primary indication for surgery. Noncompliance with prescribed treatment is a frequent cause of failure and even stricture unresponsive to dilation. With PPIs, most patients' symptoms can be controlled for long periods of time. Current recommendations for surgical intervention include:

Operations for GERD attempt to prevent reflux by mechanically increasing LES pressure and, in most procedures, to restore a sufficient length of distal esophagus to the high-pressure zone of the abdomen. Hiatal hernia, when present, is reduced simultaneously.

Laparoscopic/ minimally invasive surgical procedures are now standard of care…

All of the procedure eliminate GERD in almost 95% of patients who are followed for 10 years. But the Nissen fundoplication wins in comparison studies. Recurrent symptoms should be thoroughly worked up because they are frequently associated with other disorders and not recurrent GERD.

This condition is due to degeneration of the myenteric nerve plexus so that there is a failure of peristalsis and of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. It can present at any age but usually presents between 30 and 60 years of age. It is more common in women, the male-to-female ratio being 2 to 3, and there is a risk of malignancy in the long term.

The usual symptoms are progressive dysphagia, weight loss, and aspiration pneumonia. Management The diagnosis is made by:

Medical treatment is usually ineffective. Pneumatic dilatation of the sphincter may give temporary relief, but surgery (laparoscopic Heller's cardiomyotomy, which divides the lower esophageal sphincter to the level of the mucosa) provides the best results. Recently POEM has promising results.

This Can Occur:

The symptoms are sudden onset of pain in the chest, upper back, and neck. The patient may develop circulatory collapse, pyrexia, and emphysema in the supraclavicular region of the neck due to the escape of air.

A chest radiograph may show mediastinal air, a left pneumothorax, or fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Water-soluble contrast study confirms the site of rupture.

If the underlying problem is benign, then surgical treatment may be performed to resect or repair the damaged esophagus. Nonoperative treatment may be attempted in selected patients. (i.e., those with early small perforations and those unfit for major surgery). The patient is placed on NPO status, and intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and parenteral nutrition are prescribed. A chest drain is inserted to drain the infected pleural space. If the patient's condition deteriorates, surgery should be considered.

The risk factors for developing esophageal cancer

Both alcohol and tobacco increase the risk of carcinoma of the esophagus by a factor of 10. Additional risk factors include Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia, carcinogen exposures (e.g., nitrosamines in the Eastern world), vitamin and trace element deficiencies, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

The epidemiology of carcinoma of the esophagus

Esophageal cancer accounts for 1% of all cancers and 2% of cancer-related deaths. Generally, it is three times more common in men and occurs most commonly in the seventh decade of life. Worldwide, 95% of all esophageal cancers are of squamous cell origin; however, in the Western world, the relative incidence of adenocarcinoma has increased dramatically over the past 20 years because of the comparable increase in the incidence of Barrett's esophagus.

The most common presenting symptoms of esophageal cancer.

Dysphagia occurs in 85% of patients. Others symptoms include weight loss (60%), chest or epigastric pain (25%), regurgitation of undigested food (25%), hoarseness caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement (5%), cough or dyspnea (3%), and hematemesis (2%).

The diagnostic work-up for patients presenting with these symptoms

Benefits

This is chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both to the primary lesion before surgical resection.

The Benefits include:

The surgical options for treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus

Surgery alone or combined with chemoradiotherapy offers the only hope for cure.

The risks of surgery

The natural history of esophageal cancer

In a collected series of almost 1000 untreated patients, the 1- and 2-year survival rates were 6.0% and 0.3%, respectively. Untreated patients typically succumb to progressive malnutrition complicated by aspiration pneumonia, sepsis, and death. Formation of a fistula between the aorta or pulmonary artery and the esophagus or pulmonary tree is a somewhat more dramatic (or perhaps merciful) mode of exit. Treated or untreated, esophageal cancer is a bad disease.

"R0" (or "R zero") resection, and how does it impact survival?

All gross disease is removed, and microscopically, the margins of resection are negative for tumor. Achieving an R0 resection is the surgeon's goal and is the most robust predictor of a favorable outcome after surgery for esophageal cancer. An R1 resection represents removal of all gross disease, yet resection margins are microscopically positive for tumor. The overall 5-year survival (any stage) for patients with microscopically positive margins decreases by an order of magnitude (e.g., 30% down to 3%).